Agroforestry and Silvopasture

Agroforestry is defined as the deliberate integration of trees with crops and/or livestock, either simultaneously or sequentially on the same unit of land. Silvopasture is a category of agroforestry in which trees are integrated with grazing animals to create a managed woodland pasture. There are two ways to achieve a silvopasture, either by planting trees in a pasture or by thinning a forest enough to establish pasture plants. The aim is to have enough trees to secure the benefits that trees bring but to manage them, so they do not over-shade the pasture. In typical silvopasture systems, the trees are productive; either producing and timber crop or a fruit or nut harvest. But the real benefits are the improvements in soil health and animal welfare.

‘How to establish silvopasture on a farm & why do it’

By Clive Bright

Agricultural Benefits

Improved animal health is a significant benefit of silvopasture. Shelter, shade and access to browse are the three main advantages; all three help improve animal growth rates. The micro-climate under an open canopy of trees, especially when intersected with denser shelterbelts or hedges, is much less variable as it buffers against extreme weather events. If an animal has to expend less energy maintaining their core body temperature, that energy goes into weight gain, ensuring better welfare and profit. Sheep with adequate shelter and shade have shown a 10 – 15% greater weight gains than those without. Equally, shade in hot weather helps to regulate body temperature, which should equate to consistent weight gain. Well-spaced trees spread throughout the pasture allows animals to continue grazing and gaining weight during hot weather. If trees are sparse, animals tend to bunch around them, seeking the comfort of shade – this reduces their tendency to spread out in the pasture to graze. In exposed sites without any shade, animals become heat-stressed and do not feed to their potential; again, dramatically reducing the potential growth rate.

The shade effect is not only beneficial to the livestock – the pasture also thrives with some protection. The oldest silvopasture research site on the island of Ireland was established 1989 at Loughgall in Co. Antrim. It is composed of Ash trees over sheep pasture. During the drought of 2018, there was no reduction in grass growth at Loughgall. On average sheep were able to graze 17 weeks longer per year compared to the flock on the control site without trees.

One area of active research is the browse benefits of different tree species. The roots of trees can access and accumulate minerals from much deeper in the soil than most pasture plants. Willow leaves, for example, have cobalt and zinc in high concentrations. Lambs are particularly vulnerable to cobalt deficiency. Allowing lambs access to willow browse in summer, especially during weaning, has been shown to improve growth rates. The good news does not stop there. Secondary compounds or tannins in willow have anti-parasitic properties and also have a reductive effect on methane production in the rumen. Willow is just one example. Other palatable native species such as hazel and lime have been heavily researched for their browsing benefits.

Silvopasture is compatible with fruit, nut and timber production. Grazing can serve as a cost-effective vegetation and weed control method once the trees are strong enough and appropriate livestock are used. With trees that produce fruit or nuts, windfalls can add another layer of diversity to livestock’s diet, and by consuming unharvested fruits, the livestock help to prevent pests and diseases from spreading in the trees.

Ecological Benefits

Silvopasture has been found to increase wildlife abundance and diversity. It can provide a wide range of food and habitat for wildlife, adding structural and biological diversity to the landscape. Trees spread across the landscape can also play a considerable role in flood mitigation and water purification. Tree roots open up the soil profile and allow water to percolate in. They have associations with beneficial fungi which clump soil aggregates together and give the soil its structural ‘crumb’. Trees capture and recycle nutrients leached below the pasture rooting zone and build deeper soil organic matter through leaf-fall and root-exudates. In every way, trees increase the sponge-like, water-holding qualities healthy soil should have – this can play a huge role in reducing flood risk in catchment areas. Trees are a vital component of a functioning water cycle, by both improving infiltration but also as a physical water pump; sucking up water and transpiring it through their leaves.

Climate Benefits

Trees grown across the landscape can have a beneficial effect on both the local and broader climate through their role in cycling greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, methane and ammonia, as well as the often-overlooked water vapour. Well-spaced trees add another dimension to the solar energy captured on a given area of land. Solar energy photosynthesising through plants is the only way to build soil carbon. More layers of green leaves equate to more carbon cycling. ‘Project Drawdown’ is a global research organisation that identifies, reviews, and analyses the most viable solutions to climate change: silvopasture ranked #9 in the top 100 most effective solutions to climate change.

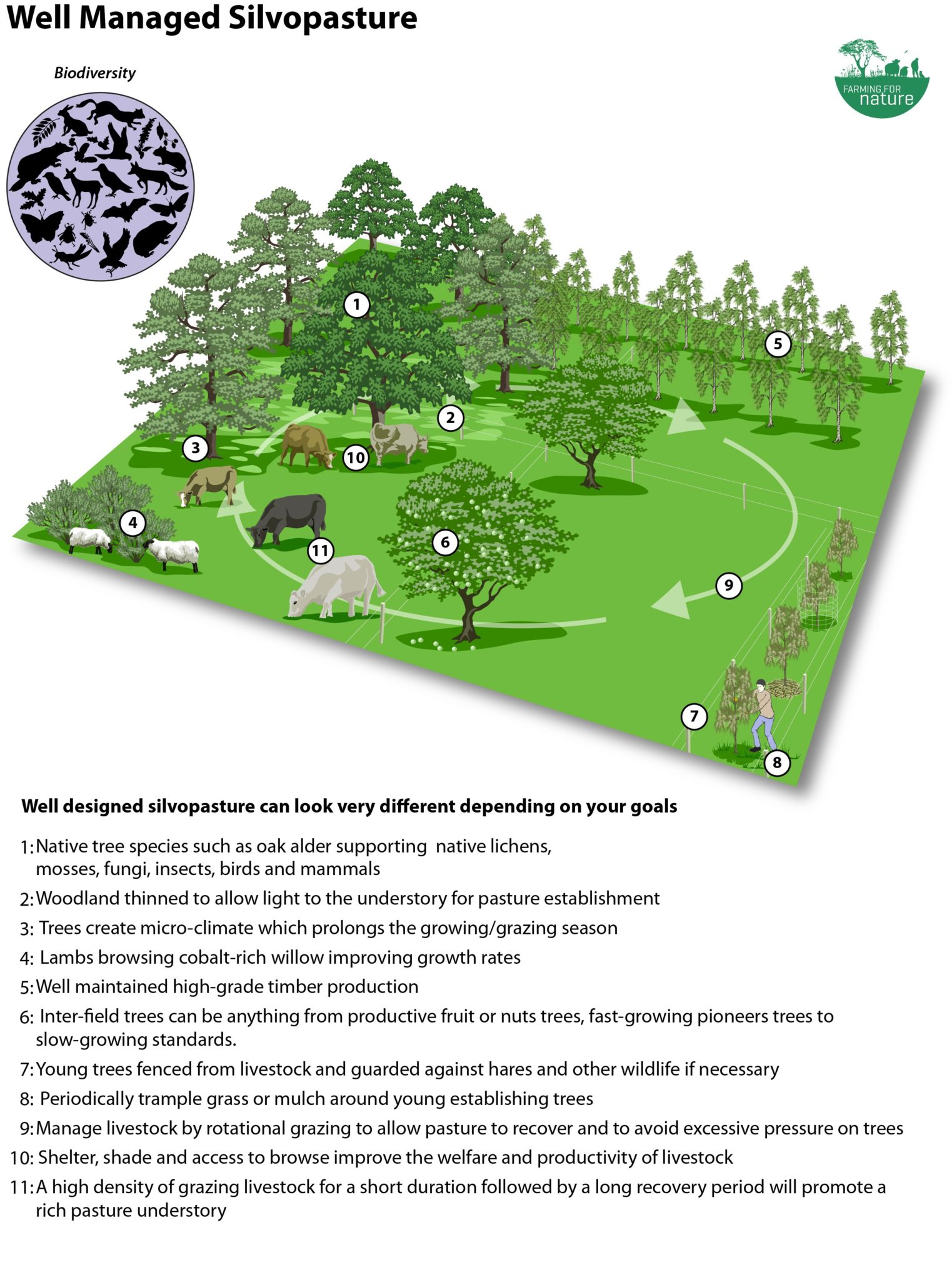

What does a well-managed silvopasture look like?

What a good silvopasture looks like is down to the goals of the farmer. Key to any silvopasture working well is managed rotational grazing. The trees and the pasture should not be continually exposed to livestock pressure and they should have an adequate recovery time after a grazing event. In an ideal world, the tree cover would be spread relatively evenly across the landscape so that animals do not huddle around favourite areas damaging the pasture and compacting the ground around trees. But even without this scenario, livestock can be managed to gain the benefit of the trees without doing damage.

Depending on the goals of the farmer, the soil type and the topography, silvopasture can look very different. Trees can be planted in regimented rows to produce timber, for example, or they can have a more natural ‘organic’ appearance if soil restoration on marginal ground is the goal.

Wakelyns is a silvoarable research site in the UK, and it provides an example of rows of short rotation coppice trees, willow and hazel, which are harvested on a five-year rotation. The coppice wood is chipped and used to heat the farmhouse. This idea could be utilised for livestock too, providing quick-growing shelter, a mineral-rich browse and a harvestable coppice crop.

How do I create a silvopasture?

1) Planting trees into existing pasture

- Planting trees in a pasture can limit the ability to use that land for other purposes in the future, so it is essential to plan how you want to see it in 20+ years. First, consider your goals and capitalise on ways of letting nature do the work for you. Establishing trees is expensive and time-consuming and potentially costly to reverse, so getting the right tree in the right place is vital. Examples of suitable trees for Silvopasture: here is no limit to the trees suited to different applications of silvopasture: Everything including fruit and nut trees, towering oak trees, shrubby hazel. There has been a lot of research done on willow, especially as a browsing plant. Standard hawthorns could work very well as inter-field trees and are fast-growing when not in a hedge. Scots pine trees make great shade umbrellas and, as they mature their impact on the understory would be minimal. Alder, birch and willow are excellent for growing on and improving marginal land. They are fast-growing and easy to manage and thin.

- The design depends on your goals for the trees and your plans for managing the pasture. Plant to suit future machinery use. If planting rows, north-south is often the best option as it allows most light to reach the ground throughout the day. Ensure the planting is not too close to buildings and potential farm development. Think about it in terms of something that you will not want to change again!

- Consider planting native trees as they support native lichens, mosses, fungi, insects, birds and mammals. Bare root trees can be planted anytime between October and March.

- Young trees may need to be watered in the first year if the ground conditions are dry. Keep young trees free from encroaching grass and bramble, especially during the first three years after planting. Simply trampling the grass around each tree, 4-5 times a year can be very effective. Mulching with woodchip is very beneficial. Prune in the first 3-5 years to shape and prevent forking of the tree.

- Make sure the young trees are protected from livestock by erecting fencing, be aware trees may take years to become productive (depending on the species). New trees can be fenced (from browsers) individually, in groups or rows. Rows are generally the most cost-effective way of fencing. Tree guards may also be necessary if hare pressure is high.

- An obvious place to start is along paddock fence lines as this cuts the fencing cost in half! For inter-field trees, a way to ensure the trees will not be in the way or limit machinery use, is to plant them in the final sward of grass in the centre of your field after you mow or top that field.

- A great way to establish rows of trees in a field is to mimic natural succession. Fence out a strip 3m wide. Plant the desired canopy trees (oaks for example) down the middle at half the final spacing, around the edges plant pioneer trees like alder, birch and willow. These pioneer trees will create the desired “tree effect” much faster than the slower-growing oak. They will also nurse the oak, which in turn will grow much faster too as the pioneers will improve the soil biology and growing conditions much faster. As a result, the trees will be able to withstand livestock pressure much sooner – the fence can be removed, and the trees thinned as necessary.

OR

2) Establishing pasture by thinning woodland

- Integrating pasture into woodland means the woodland will, most likely, need to be thinned to increase light infiltration. Thinning is time-consuming and may require heavy machinery, as well as a strategy for dealing with felled trees. Thinned woodlands are also likely to experience a flush of growth in weeds (bramble, bracken etc.) and seedling trees that must be dealt with to prevent the pasture from being overgrown. Pasture forages may also need to be established beneath the trees, a process which can be difficult if trees have already been felled. Rotating livestock quickly at a high density through a thinned woodland can help to stimulate pasture growth and knock back weeds and woody regrowth.

- Select the healthiest most vigorous trees to keep, favour native species but also aim to preserve the broadest range of diversity in age and species. Remove any weak or diseased trees. It may be wise to thin in stages over several years. After the first thinning, introduce the livestock at a high stocking rate for a short time (1 day per area). The livestock will help clear undergrowth by browsing and trampling and will also stimulate pasture growth. Observe the canopy cover and mark the trees for the next thinning.

- If the ground conditions are right, feeding animals by rolling hay from diverse pastures in recently thinned woods can be a cost-effective way to introduce seed to kick-start pasture growth. Care should be taken not to damage the ground or the trees; livestock should be rotated through and not left in an area for too long.

Avoid

- Avoid unmanaged grazing in woodlands and silvopasture systems as it can have a severe impact on the trees, the soil and the broader environment.

- Avoid planting in sensitive habitats, where trees could upset the natural ecology.

- Avoid fertiliser or herbicide applications near the roots and canopies of the trees to allow for natural biodiversity to increase.

Top Tip from the Farmer

With Silvopasture, design and planning are everything, make sure you know your goals and why are you planting silvopasture. Plan for soil type, aspect, function and machinery use – a tree in the way will have a short life! Plus I highly recommend the following resource The Soil Association’s The Agroforestry Handbook

About Clive Bright

More information and a short film on Clive’s farm here. Ambassador since 2019